On walkability, part 3: Things I learned in the UK

I’ve been meaning to get back to the walkability series (part 1; part 2) for a while, particularly after my walking-intensive summer vacation. Here are a few things I noticed on the great Scotland-to-England journey of 2010:

1. Street usability

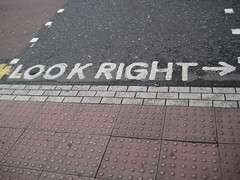

One of the things that impressed me a lot about London, during my three days there, was the level of usability built into street infrastructure. Clearly, someone has been thinking about making the streets of London pedestrian-friendly. Consider, for instance, curbside signage:

UK traffic is on the opposite side of the road from many other countries, and if you’re visiting from one of those countries, it’s all too easy to forget which way to look as you step into an intersection into oncoming traffic. So in a lot of places, you see these directional signs painted right next to the curb. I particularly appreciated the arrows, as I am one of those people who can’t tell right from left without stopping to think about it.

The other thing I appreciated immensely: not only do the “You Are Here” map kiosks in central London offer detailed maps, the maps are oriented so that whichever direction you face as you’re looking at the kiosk is the direction that points upward on the map. This made map-reading so intuitive (how many times have you squinted at a dot on a map kiosk and tried to figure out which of a confusing tangle of streets is the one right in front of you?) that I wondered why this isn’t the standard practice everywhere. (I’m looking at you, Boston, City of Total Disorientation.)

2. Intersection density

A while back, I came across a blog post about a study that found intersection density—the number of street intersections per square mile, typically much higher in older, denser cities than in newer suburbs—to have a surprisingly high impact on overall walkability. It’s one of those things that aren’t immediately obvious but make a lot of sense when you think about them. The greater the number of intersections, the more possible routes there are, the less often pedestrians will have to take the long way around, and the easier it is to vary one’s route and avoid boredom.

Old Town in Edinburgh is full of tiny narrow alleys, or “closes,” that break up longer blocks of buildings and increase the overall number of intersections quite a bit. Some of them are wide enough that they’re open to car traffic; others are for foot traffic only; and some consist of a flight of stairs, sometimes sheltered by the upper storeys of adjacent buildings and sometimes open. They have wonderful names, too: World’s End Close, Writer’s Close, Sugarhouse Close. This is Fleshmarket Close (there’s also a Fishmarket Close nearby):

One caveat: I don’t know how safe the closes are after dark; I wasn’t out all that late while I was there. But during the day, I loved having a set of built-in shortcuts all over the city.

3. Walking culture

It’s not that people don’t hike for fun in the States. But the UK has much more of a culture of recreational walking,* with a whole history of walkers’ associations and disputes over public rights of way. My time in the Lake District, an especially popular walking destination, made that clear: every town I visited had a tourist center that offered directions and sold Ordance Survey Explorer maps and Kendal Mint Cake, the hill-walker’s favorite snack. Outdoor stores were everywhere, peddling breathable clothing, sturdy boots, compasses, and mountaineering equipment. And I kept meeting fellow walkers of all ages everywhere.

The big cities I visited had spaces for taking a rural walk as well: Edinburgh’s Holyrood Park, with scores of people strolling the paths and bluffs, and Hampstead Heath in London, which on a sunny July afternoon was full of wanderers and picnickers. Recreational walking seemed there to be more about enjoying the surroundings than about getting Serious Exercise, although there’s certainly some of that as well. (Rebecca Solnit makes much the same point in Wanderlust: A History of Walking, which I’m currently reading.)

Most of all, I loved that I could walk right to the edge of a town like Grasmere or Keswick and keep going, on side roads or paths through fields, up the side of a fell or all around a lake, and on for as many miles as my feet could take me. Whereas on this side of the pond, if you want to go for a long semi-rural walk—at least in my part of the US—you generally have to drive there first.

* See this post on the walking habits of Wilkie Collins on one of my new favorite blogs, Steamboats are ruining everything. While visiting New York, Collins found that his daily walks puzzled the natives:

Biographer Catherine Peters reports that during an 1873 book tour of America, Collins was dismayed to discover that Americans did not carry walking-sticks and did not like to go on walks. From New York, Collins wrote home to a friend of his chagrin:

I . . . thought nothing of a daily constitutional from my hotel in Union-square to Central Park and back. Half a dozen times on my way, friends in carriages would stop and beg me to jump in. I always declined, and I really believe that they regarded my walking exploits as a piece of English eccentricity.

I’ve had the exact same experience more times than I can count, only with much shorter distances than Collins’ five-mile Union Square to Central Park stroll.

Oh, my gosh, map (dis)orientation is one of my biggest pet peeves. I mean, even if you’re going to make identical maps, with the same direction at the top of each, you can still mount them on walls or posts or whatever such that you’re not trying to figure out directions by tilting your head or playing spatial games in your brain.

I also agree that the “look right” arrow is awesome. After visiting Australia, my sense of which way to look first is almost completely broken, and I have trouble with left and right anyway. So, yay, sign!